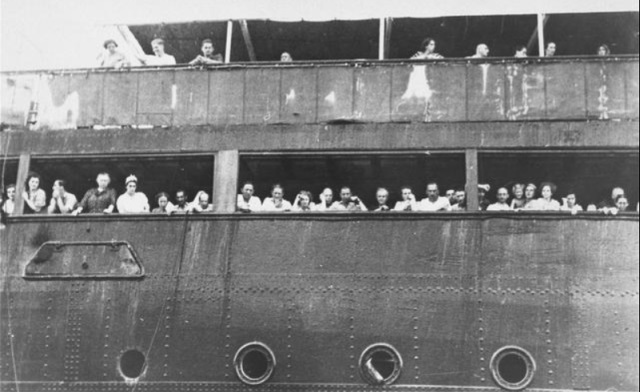

Jewish refugees aboard the SS St. Louis attempt to communicate with friends and relatives in Cuba, who were permitted to approach the docked vessel in small boats. Photo Courtesy: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

By Nora Gámez Torres

ngameztorres@elNuevoHerald.com

When 937 Jewish refugees boarded the transatlantic SS St. Louis on May 13, 1939 in Hamburg, Germany, to travel to Havana, they thought the voyage would at long last free them of Nazi persecution. But for many, the journey was doomed to fail because of strong anti-immigrant sentiment that prevailed in Cuba.

Most of the refugees crossing the Atlantic never made it to land, and many ended up facing death in a European concentration camp.

To commemorate the 75th anniversary of the ordeal, the Jewish Museum in Miami recently hosted a panel that examined the facts surrounding the St. Louis voyage and shared new information on the issue.

The event—organized by Florida International University's Latin American and Caribbean Center (LACC), Holocaust Studies Initiative, and Cuban Research Institute (CRI)—brought together Scott Miller, head curator of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum; Herb Karliner, survivor of the St. Louis; Frank Mora, director of LACC, and Margalit Bejarano, historian and emeritus professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

According to the panel, the boat arrived in Cuba in the middle of a complicated political and economic climate. The official Cuban immigration policy at the time was marked by strong nationalism, and foreigners were perceived as threats to employment. The Nationalization of Employment Law of 1933 was a big blow to immigration, for it established that 50 percent of workers at every company had to be Cuban nationals.

According to the daily newspaper El Mundo of May 23, 1939, while the St. Louis was still crossing the Atlantic, the Cuban Treasury Department planned to add an amendment to the law banning the landing of "individuals who were born in or were from Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Germany, Turkey, Romania, Russia, China, Jamaica, Haiti, and Japan."

In that context, the government of then-Cuban President Federico Laredo Brú was under an intense anti-immigration campaign, bordering on anti-Semitism, by the Cuban media.

A Diario de la Marina editorial on May 14, 1939, called on the government to stop the "immigration flood that has descended upon our country. If we continue our policy of half-open doors, if not completely open, to the numerous European refugees, we will soon begin to feel the consequences. … It will not be long before they find what they are seeking: employment. And thus the unemployment problem will intensify. Shortly after, protests will rise. … We have to look after our own house. … This is not about xenophobia but about prudence."

Historian Bejarano said that the media campaign had been sponsored by the Gestapo. The organization went as far as recruiting Juan Prohías, who had founded the Cuban Nazi Party and disseminated anti-Semitism on radio and other media.

Bejarano said the St. Louis voyage, as well as the anti-immigration media campaign, was orchestrated by the German Ministry of Propaganda to sway international opinion and show that Nazi Germany allowed Jews to leave freely—while at the same time fomenting hostile receptions in other countries.

The St. Louis passengers were trapped in a power struggle between President Brú and Col. Fulgencio Batista, who was then the Army's commander in chief and protector of Col. Manuel Benítez, director of immigration. A fourth player was Secretary of State Juan J. Remos, who opposed Benítez's corruption.

Cuba was becoming a transit stop for Jewish refugees, most of whom hoped to enter the United States. The U.S. government had established a quota system that regulated the number of immigrants by nationalities and many Jews were to arrive in Cuba to wait for their visas.

On the part of Cuba, the official process to obtain an immigrant's visa required a $500 bond to be handed to Benítez, who had to sign his approval before the shipping company could sell the fares. The Cuban State Department had to review the permit issued by Benítez and investigate the financial situation of every immigrant before extending their visas.

Facing the possibility of an outburst of refugees escaping Fascism, Benítez saw the opportunity to get rich and decided to sell tourist visas for $150. Official documents show that he issued 5,000 visas for Jewish immigrants between January and April that year. It is known that a good part of that revenue was earmarked to military schools under Batista.

However, on May 5, President Brú handed a big blow to that business when he signed Law Decree 937, which established that all foreigners, including tourists and people in transit, wanting to enter the country—with the exception of U.S. citizens—had to deposit $500 besides obtaining a "personal visa" authorized by the departments of State, Labor, and Treasury to be stamped at Cuban consulates abroad.

When the boat sailed on May 13, most of the refugees aboard the St. Louis had permits acquired for $150 from Benítez, who had assured the German shipping company Hapag that the new decree would not affect its passengers. But the fate of the St. Louis had been sealed on May 5.

The Fate of the St. Louis Passengers

Upon the boat's arrival at the Port of Havana in the early hours of May 27, Brú had issued a special order prohibiting its entrance to the port and a police patrol boat escorted it to a roadstead. Only 22 refugees could change their permits for regular visas after paying $500 and were able to land. Another passenger attempted suicide by cutting his veins and jumping into the water, while another six obtained last-minute visas thanks to arrangements made by the Cuban ambassador to the United States.

Karliner, the St. Louis survivor on the panel, talked about the anguish among the passengers after their entrance was denied. "There were rumors of a possible wave of suicides," he said.

But the St. Louis was not the only boat carrying Jewish refugees to Havana. The Orduña left Liverpool, England, on May 11 and arrived in Havana also on May 27. It carried 68 refugees whose documents were accepted by the Cuban authorities, but another 72 could not disembark.

The next day, on May 28, authorities also denied another boat, the Flandre, permission to dock. Only six Jewish passengers who had legal visas were allowed to come ashore.

On May 30, Lawrence Berenson, an envoy from the New York-based American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, arrived in Havana to convince the Cuban government to allow the refugees from all three boats to enter the country.

However, on June 2, the St. Louis was forced to abandon Cuban waters with 907 refugees remaining aboard. Many had relatives already in Havana who came near the ship on a small boat to say goodbye, shouting, "You will not be returned to Germany!"

On June 5, the Miami Herald's morning edition published a photograph locating the St. Louis close to Miami Beach. Apparently, the captain of the boat, Gustav Schröder—a German who witnesses said cared for the treatment and destination of his passengers— brought the vessel closer to Miami's shores, hoping to receive help from the United States.

As the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum's webpage explains, the U.S. Coast Guard patrolled the waters to prevent anyone from jumping overboard or the captain from docking. But the U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office has denied that version, saying that there were no orders to intercept the boat. The Coast Guard was there only to protect the passengers' lives, it said.

Many of the refugees had already applied for visas in U.S. consulates in Europe. However, Franklin D. Roosevelt's government insisted that they had to wait until the visas were granted before being allowed into the country.

Mora, LACC's director, pointed at some facts that could help to provide a context to the United States’ refusal to accept the refugees. Among them, he mentioned the unfavorable political climate for immigration, the 1938 economic recession and the fact that Roosevelt did not want to upset voters, as he was considering an unprecedented political move: a third term.

Unable to dock in Florida, Schröder headed again to Cuba, where he hoped that Berenson's continuing efforts with the Cuban government had produced positive results.

Officials asked Berenson for $150,000 as a guarantee, which also included the passengers of the other two boats. Then they demanded payment of the official visa ($500 per person), which raised the figure to close to a half-million dollars.

Berenson was committed to pay more than half of that amount immediately, and a hopeful moment emerged when President Brú announced that he was willing to grant temporary asylum to the passengers in a transit camp on the Isle of Pines, south of Havana province.

Berenson made an appeal to the media, published also by the Diario de la Marina: "Gentlemen, have mercy on these poor people. They have already received enough punishment and you should look at them with compassion. They will not break any law in this country and we, in the Committee, assure you that they will not be a public burden."

However, after a closed-door meeting between Brú, Col. Batista, and other officers on June 6, the Cuban government blamed Berenson for not complying with an alleged 48-hour ultimatum to deliver the cash bond and therefore declared the St. Louis case closed.

Thanks to efforts made by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the boat did not return to Germany but to Belgium. The Belgian government, as well as those of Holland, France, and England, accepted the Jews. But by 1940, the passengers, except those who found shelter in the United Kingdom, found themselves again under the Nazis' control.

Miller and Sarah Ogilvie, of the Holocaust Museum, were able to track down many of the passengers. About 80 made it to the United States before 1941 after they received their immigrant visas. Others, less fortunate, were sent to concentration camps. More than 200 died in the Holocaust.

Miller and Ogilvie estimate that of the 620 passengers who returned to the European continent, 365 survived the war, among them Karliner, who arrived in France and was able to fool the Nazis pretending to be a French Catholic. Many years later, he returned to Miami Beach as a master baker.